A Mexican Mother’s Search for Justice

by José Espericueta

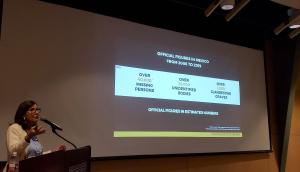

In early October, Lucía Díaz, founder of Colectivo Solecito, and Dr. Matt Hone, an independent researcher, came to Dallas from Veracruz, Mexico to talk about the thousands of disappeared victims of the country’s ongoing drug violence. The particular event that I helped to organize was in collaboration with Doctors Nils Ackerman and Pedro Gonzalez Corona from the University of Texas at Dallas’s Holocaust Studies Center. It was hosted by the University of Dallas and funded in part by the Dallas Peace and Justice Center.

Lucía told the painful story of the disappearance of her son. In 2013, her son Guillermo, a popular DJ with no connection to the drug cartels in Veracruz, was kidnapped and then disappeared. What makes this all the more heartbreaking is noting that Lucia’s wounds have yet to heal because she knows nothing about his whereabouts. Moreover, she has received little help from law enforcement or government officials. The work to find Guillermo has been undertaken by Lucía and mothers like her because this is not just her story, but that of thousands of other mothers whose children have also disappeared throughout Mexico, most of whom are innocent victims of the country’s drug violence.

Rough estimates put the number of disappeared around 40,000. But this number is likely far greater simply because family members are too scared to reach out to police that may be both corrupt and intertwined with powerful drug cartels. Lucía has left her job as a university professor to form Colectivo Solecito (“Little Sun Collective”) and work with other mothers who are searching for information regarding their children. Much of this work involves following tips, digging for mass graves, and providing a support network for the families of those disappeared. They do work that the police refuse to do, risking their own lives in a search for both justice and closure.

Last month, ABC News aired a series exploring both Lucía’s story and the Mexican government’s response. It is worth watching and considering. One of Lucía’s biggest requests when she spoke at the University of Dallas was simply that we share her story and that we make it as well-known as possible. Spreading awareness of her case and the cases of the thousands of victims throughout Mexico could help to increase international pressure on the government to act and support organizations like Colectivo Solecito.

But we must do more than just listen, and our gaze should not be fixed on Mexico alone. As much as this is Mexico’s problem, it is also our own. If we truly seek to understand the causes of “drug violence” we must continually reflect on the fact that Mexico shares a border with the largest consumer of drugs and the largest producer of weapons in the world. The drug trade exists primarily to traffic drugs northward to the United States for the habits and addictions of millions of Americans. And while treatment should be prioritized over policing, we must also give greater thought to the many benefits of widespread legalization. None of this removes any of the blame from violent cartels or corrupt officials. But if we are to truly realize our interconnectedness as members of the human race, we must share responsibility in solving this problem.

Additional information (en Español):

www.sinembargo.mx